Consensus

All blockchains require some type of consensus mechanism to agree on the blockchain state. Because Substrate provides a modular framework for building blockchains, it supports a few different models for nodes to reach consensus. In general, different consensus models have different trade-offs, so selecting the type of consensus you want to use for your chain is an important consideration. The consensus models that Substrate supports by default require minimal configuration, but it's also possible to build a custom consensus model, if needed.

Consensus in two phases

Unlike some blockchains, Substrate splits the requirement to reach consensus into two separate phases:

- Block authoring is the process nodes use to create new blocks.

- Block finalization is the process used to handle forks and choose the canonical chain.

Block authoring

Before you can reach consensus, some nodes in the blockchain network must be able to produce new blocks. How the blockchain decides the nodes that are authorized to author blocks depends on which consensus model you're using. For example, in a centralized network, a single node might author all the blocks. In a completely decentralized network without any trusted nodes, an algorithm must select the block author at each block height.

For a Substrate-based blockchain, you can choose one of the following block authoring algorithms or create your own:

- Authority-based round-robin scheduling (Aura).

- Blind assignment of blockchain extension (BABE) slot-based scheduling.

- Proof of work computation-based scheduling.

The Aura and BABE consensus models require you to have a known set of validator nodes that are permitted to produce blocks. In both of these consensus models, time is divided up into discrete slots. During each slot only some of the validators can produce a block. In the Aura consensus model, validators that can author blocks rotate in a round-robin fashion. In the BABE consensus model, validators are selected based on a verifiable random function (VRF) as opposed to the round-robin selection method.

In proof-of-work consensus models, any node can produce a block at any time if the node has solved a computationally-intensive problem. Solving the problem takes CPU time, and thus nodes can only produce blocks in proportion with their computing resources. Substrate provides a proof-of-work block production engine.

Finalization and forks

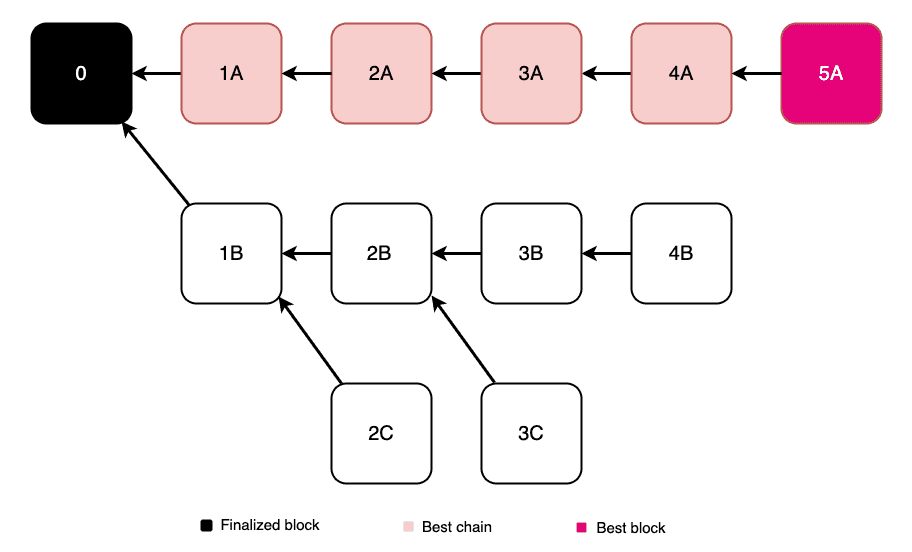

As a primitive, a block contains a header and transactions. Each block header contains a reference to its parent block, so you can trace the chain back to its genesis. Forks occur when two blocks reference the same parent. Block finalization is a mechanism that resolves forks such that only the canonical chain exists.

A fork choice rule is an algorithm that selects the best chain that should be extended.

Substrate exposes this fork choice rule through the SelectChain trait.

You can use the trait to write your custom fork choice rule, or use GRANDPA, the finality mechanism used in Polkadot and similar chains.

In the GRANDPA protocol, the longest chain rule simply says that the best chain is the longest chain.

Substrate provides this chain selection rule with the LongestChain struct.

GRANDPA uses the longest chain rule in its voting mechanism.

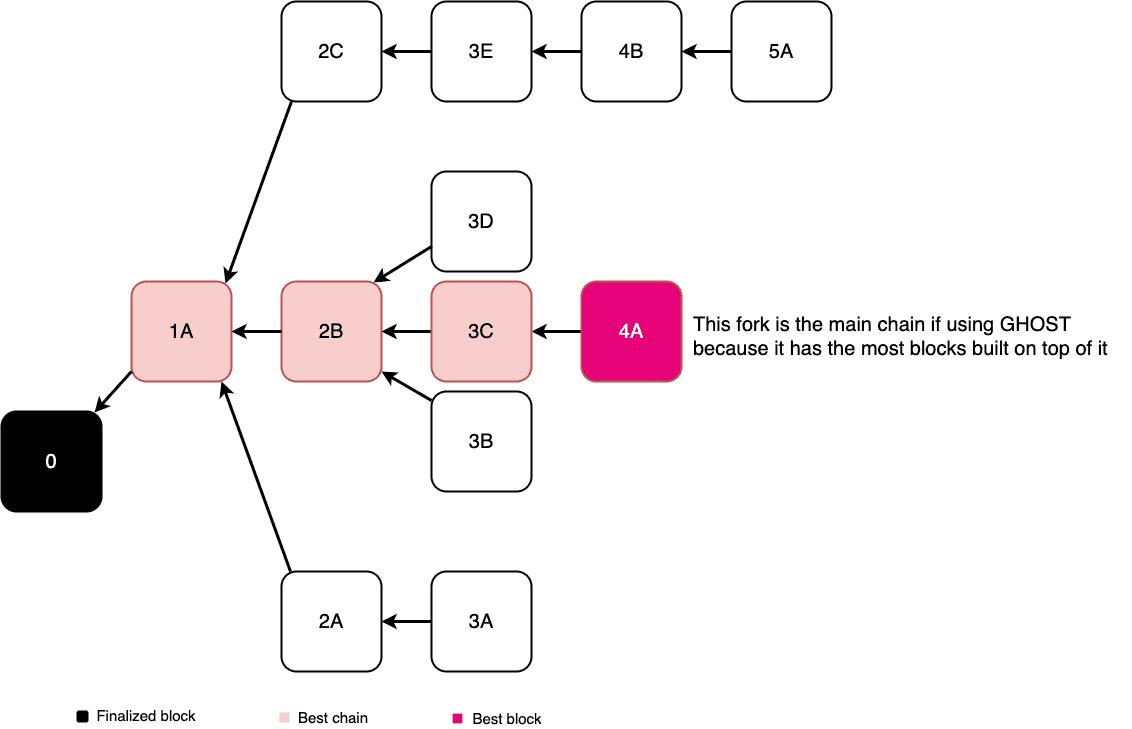

One disadvantage of the longest chain rule is that an attacker could create a chain of blocks that outpaces the network and effectively hijack the main chain. The Greedy Heaviest Observed SubTree (GHOST) rule says that, starting at the genesis block, each fork is resolved by choosing the heaviest branch that has the most blocks built on it.

In this diagram, the heaviest chain is the fork that has accumulated most blocks built on top of it. If you are using the GHOST rule for chain selection, this fork would be selected as the main chain even though it has fewer blocks than the longest chain fork.

Deterministic finality

It's natural for users to want to know when transactions are finalized and signaled by some event such as a receipt delivered or papers signed. However, with the block authoring and fork choice rules described so far, transactions are never entirely finalized. There is always a chance that a longer or heavier chain might revert a transaction. However, the more blocks are built on top of a particular block, the less likely it is to ever be reverted. In this way, block authoring along with a proper fork choice rule provides probabilistic finality.

If your blockchain requires deterministic finality, you can add a finality mechanism to the blockchain logic. For example, you can have members of a fixed authority set cast finality votes. When enough votes have been cast for a certain block, the block is deemed final. In most blockchains, this threshold is two-thirds. Blocks that have been finalized cannot be reverted without external coordination such as a hard fork.

In some consensus models, block production and block finality are combined, and a new block N+1 cannot be authored until block N is finalized.

As you've seen, in Substrate, the two processes are isolated from one another.

By separating block authoring from block finalization, Substrate enables you to use any block authoring algorithm with probabilistic finality or combine it with a finality mechanism to achieve deterministic finality.

If your blockchain uses a finality mechanism, you must modify the fork choice rule to consider the results of the finality vote. For example, instead of taking the longest chain period, a node would take the longest chain that contains the most recently finalized block.

Default consensus models

Although you can implement your own consensus mechanism, the Substrate node template includes Aura for block authoring and GRANDPA finalization by default. Substrate also provides implementations of BABE and proof-of-work consensus models.

Aura

Aura provides a slot-based block authoring mechanism. In Aura a known set of authorities take turns producing blocks.

BABE

BABE provides slot-based block authoring with a known set of validators and is typically used in proof-of-stake blockchains. Unlike Aura, slot assignment is based on the evaluation of a Verifiable Random Function (VRF). Each validator is assigned a weight for an epoch. This epoch is broken up into slots and the validator evaluates its VRF at each slot. For each slot that the validator's VRF output is below its weight, it is allowed to author a block.

Because multiple validators might be able to produce a block during the same slot, forks are more common in BABE than they are in Aura, even in good network conditions.

Substrate's implementation of BABE also has a fallback mechanism for when no authorities are chosen in a given slot. These secondary slot assignments allow BABE to achieve a constant block time.

Proof of work

Proof-of-work block authoring is not slot-based and does not require a known authority set. In proof of work, anyone can produce a block at any time, so long as they can solve a computationally challenging problem (typically a hash preimage search). The difficulty of this problem can be tuned to provide a statistical target block time.

GRANDPA

GRANDPA provides block finalization. It has a known weighted authority set like BABE. However, GRANDPA does not author blocks. It just listens to gossip about blocks that have been produced by block authoring nodes. GRANDPA validators vote on chains, not blocks,. GRANDPA validators vote on a block that they consider best and their votes are applied transitively to all previous blocks. After two-thirds of the GRANDPA authorities have voted for a particular block, it is considered final.

All deterministic finality algorithms, including GRANDPA, require at least 2f + 1 non-faulty nodes, where f is the number of faulty or malicious nodes.

Learn more about where this threshold comes from and why it is ideal in the seminal paper Reaching Agreement in the Presence of Faults or on Wikipedia: Byzantine Fault.

Not all consensus protocols define a single, canonical chain. Some protocols validate directed acyclic graphs (DAG) when two blocks with the same parent do not have conflicting state changes. See AlephBFT for such an example.